Planck was launched in 2009 from French Guiana on an Ariane 5 rocket. It has a sister-experiment, Herschel, which was launched on the same rocket. Following launch, Planck will travel to a point called “L2“, short for “Lagrange Point 2”, and orbit around it. L2 is a particularly useful place to be, at around 1.5 million km (around 1 million miles) from Earth in the opposite direction to the Sun. The combined gravity of the Earth and the Sun means that anything near this location orbits the Sun in exactly 1 year, and so stays in the same place relative to the Earth.

Planck didn’t sit exactly on the L2 point, but orbited around it at an average distance of around 400,000 km (around 250,000 miles). This is important because it meant that it was never in the Earth’s shadow, so its solar panels (which provide all of the power to the satellite) could always see the Sun. Besides, it’s going to get a bit crowded up at L2 – the WMAP satellite is already there, and Planck and Herschel will also be joined in a few years by the Gaia probe and later the James Webb Space Telescope.

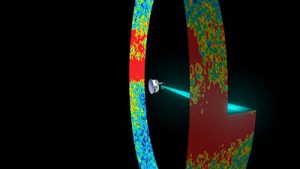

A Spinning satellite

Planck continually span around an axis pointing away from the Sun, at a rate of one revolution per minute, and looked nearly at right angles to that axis. Every minute it looked at a ring around the sky, and as it orbited the Sun the rings gradually moved round the sky. After a little over 6 months it had made a map of the whole sky, and continueed to observe for several years to make its maps even better.

End of mission

Eventually, all the Helium coolant used to cool the detectors ran out, at which time Planck stopped observing. After a few final tests, the remaining fuel was vented, pushing the spacecraft away from its L2 orbit, and the spacecraft was switched off for the final time.