The Planck satellite is not only being monitored by the mission controllers at the Mission Operations Centre. It is also being watched by optical astronomers, who have captured images of the satellite against the starry background. There are two methods of doing this, one is to stare at the area of sky which the spacecraft will pass through and watch for moving objects – this is the same method used to find near-earth objects such as asteroids and comets. The other method, which relies on more equipment, is to track where Planck should be in the sky. Since it is a moving target, travelling a little over one arcminute (1/60th of a degree) per hour relative to the background stars, taking a long exposure on a camera causes the stars to move across the field of view, creating “star trails”.

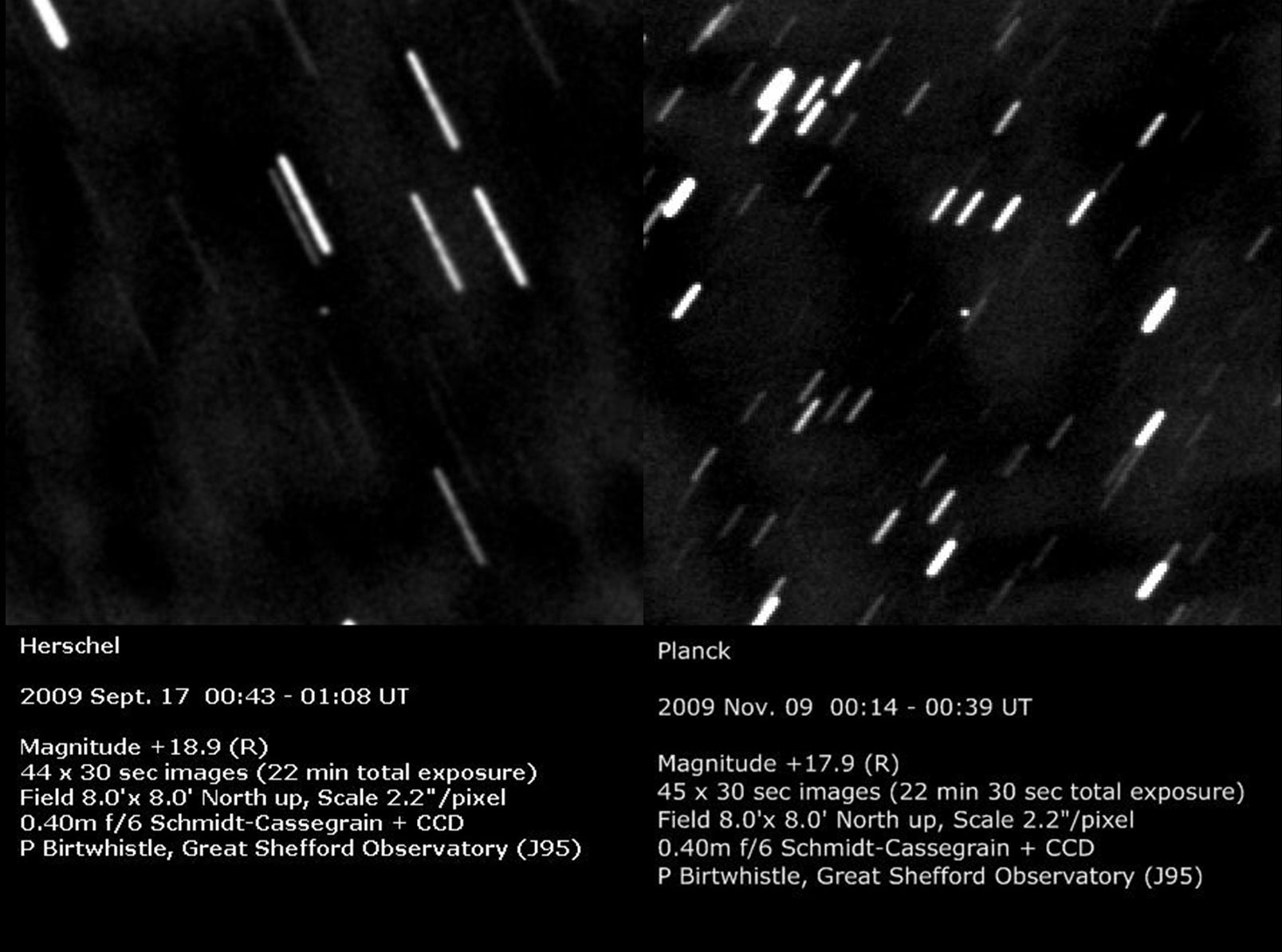

Images of Herschel (left) and Planck (right) with the background stars moving. Image credit: Peter Birtwhistle, Great Shefford Observatory

In the UK, Peter Birtwhistle of Great Shefford Obervatory in Berkshire has captured both Planck and its sister satellite Herschel, as shown on the left. Planck appears brighter despite its smaller size, which is most likely due to the angle of the solar panels causing more sunlight to be reflected back to Earth.

The satellites are both very faint, appearing at about magnitude 18-19 – that’s nearly a million times fainter than the faintest stars visible to the naked eye! To observe them, relatively large telescopes are needed, and even with a 0.4m diameter telescope such as Peter’s requires an exposure over 20 minutes long. Planck is currently towards the constellation of Perseus, as seen from Earth. It is moving at a little over 1 arcminute (1/60th of a degree) per hour as it orbits the L2 point.

Similar observations of the Herschel satellite from the Carary Islands have provided an animation of the spacecraft moving through the field of view – see here for more details.